Read all about how lightning forms, facts about lightning, and lighting safety tips!

Thunderstorms bring with them all sorts of hazards, some more common than others, but perhaps the most common phenomenon is lightning. For thousands of years, humans have been both captivated and frightened by these bolts from the heavens, so much so that they often attributed it to wrathful, angry deities.

Despite the fact that science has helped us better understand its nature, lightning still has an air of mystery and danger to it. That's why to this day, meteorologists continue to study it, not just out of a sense of wonder and curiosity, but also to help us make better decisions for the sake of safety.

So, what is lightning, exactly? What causes lightning and thunder during a storm? How does meteorology help us stay safe from lightning, and what can you do to protect yourself, your family, and your property from the next bolt-hurling thunderstorm? In our third installment of our spring storm series, we'll discuss all of this and more - read on!

What is lightning, exactly?

What is lightning and where does it come from? This is a question that humans have asked themselves since the dawn of time dawn of time, and every generation has come up with its own creative way to explain these mysterious, seemingly supernatural, flashes of light. Perhaps it's Zeus tossing bolts like javelin from Mount Olympus! Or perhaps it's Thor swinging his hammer! Maybe it has something to do with angels bowling in the clouds! Then in 1749, French physicist Jean-Antoine Nollet hypothesized that perhaps lightning was not supernatural - maybe it is electricity.

It was this line of reasoning that lead to the famous

kite experiment carried out by Founding Father Benjamin Franklin. In reality, his kite was not hit by a visible bolt of lightning - if it had, he would likely not have been around to see the birth of our nation. Instead, his kite flew beneath a thunderstorm and likely became charged by the electrical field it produced. After a spark jumped to his hand when he moved it near the key attached to the kite string, he proved that lightning was, in fact, electricity.

Modern science and meteorology have taken us much further since then. Now, we not only know that lightning is electricity - we also have a pretty good idea of how it forms inside a thunderstorm. Let's take a look!

What causes lightning?

If you've followed our previous blogs in our spring storm series, you can probably guess where we'll begin: thunderstorms! As with all severe weather,

lightning begins within a thunderstorm, and many of the same natural processes are responsible.

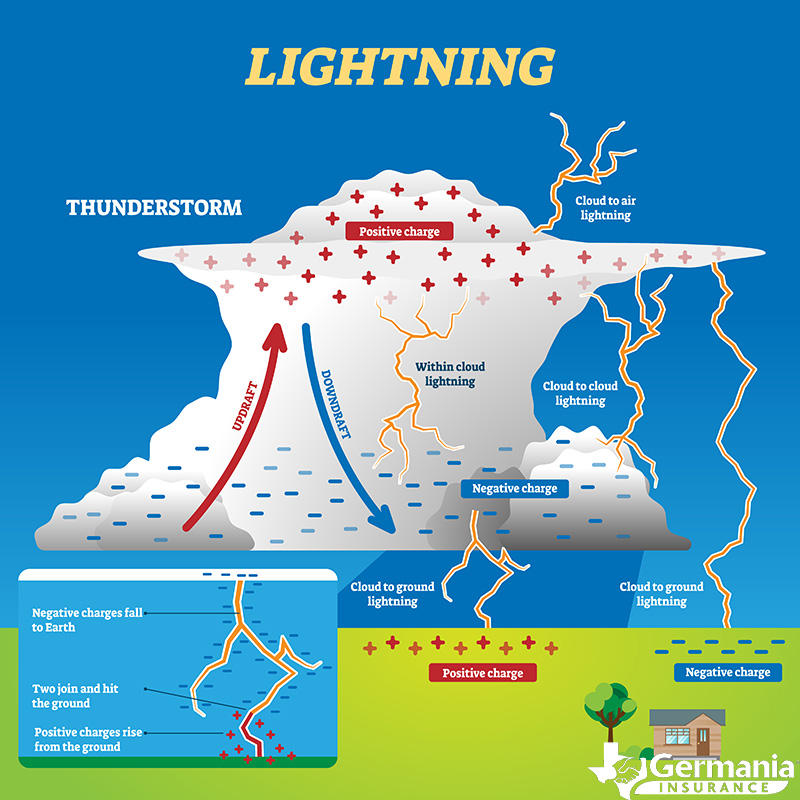

Building up a charge. Thunderstorms are caused by powerful updrafts

Building up a charge. Thunderstorms are caused by powerful updrafts - parcels or large volumes of warm moist air that rise into cooler air. The water within these parcels of air condenses into liquid droplets, and then at a certain point, freezes and falls.

Within a thunderstorm, there are countless bits of moisture in the form of

hail and graupel being lofted up by the winds only to fall back down again, or otherwise swirl around within the cloud. As all of these small droplets bump into one another and bounce around, they often snatch electrons off of one another, creating groups that are positively charged and groups that are negatively charged. A thunderstorm may have several areas of both positive and negative charges, but generally positive pools at the top and negative pools at the bottom of a cloud.

This is somewhat similar to the process you may have experienced when you walk across a rug wearing socks, and then find an unpleasant shock when you touch the doorknob. This static electricity is built up as your feet scrub against the carpet, snatching electrons that build up inside of you, which then discharges when you touch the doorknob, or any other conductive surface with an opposite charge.

Electrical fields. Similarly, the space between charged pools in a thunderstorm create powerful electrical fields. When the charge on one side becomes too great, it attempts to discharge and equalize. This discharge is lightning, which acts as a sort of bridge, allowing for the two regions to temporarily equalize before the charges build back up again.

More often than not, this takes place in between the pools of charges within a cloud; lightning forms in the electrical fields between positive and negative regions in a cloud, temporarily equalizing the two. However, as we'll discuss shortly, these electrical fields can form in between the cloud and objects on the ground, or the ground itself.

Leaders and streamers. There's a lot more to lightning that the flash we see! Before the visible bolt that we all associate with lightning occurs, a channel has to be created between the oppositely charged regions. Air is not a good conductor of electricity, so lightning needs a pathway to follow. These pathways are called "leaders."

A leader is an electrically conductive channel of ionized gas that forms in between the aforementioned oppositely charged regions in and around a storm cloud. The tip of a leader has either a positive or negative charge, which is attracted to an area in the cloud with an opposite charge (negative to positive, positive to negative). While air is normally a poor conductor of electricity, these ionized channels create a sort of pathway for energy to flow through.

Where these leaders come from, or how they begin, is not well understood, but you can think of these leaders like jumper cables on a car battery. Before a lightning strike occurs, these leaders often branch out, searching for the path of least resistance. Not all of the branches make it to where they're going before a connection is made, which is why lightning often has a fork-like appearance.

Sometimes, if an area on the ground has a strong enough pool of oppositely charged particles, it can strengthen the overall electrical field between the cloud and the ground. As leaders move towards the ground in this field, sometimes another channel can actually move up from tall objects on the ground to try and meet it.

This is called an upward streamer, and in rare footage and photos, you can often see them crawling up from the tops of towers and telephone poles just before a lightning strike. This is also the reason that people's hair begins to stand up just before they are struck by lightning.

Discharge and the return stroke. Once the leaders have made a connection and formed a pathway, the electrons are free to flow! They travel across the channels created by the leader, producing an immense flash of light known as the return stroke.

So, to summarize: Clouds make pools of oppositely charged particles, which create electrical fields in between them. Leaders form within the fields between oppositely charged pools, creating a pathway for electrons. When the leaders connect, the electrons flow along the path, creating a bright flash of light that we call lightning.

Types of lightning

Now that we've discussed and hopefully explained how lightning works, let's take a look at some of the different types of lightning you might see.

Intra-cloud (IC) and cloud-to-cloud (CC). As mentioned, lightning that occurs within a single cloud, or intra-cloud lightning, is the most common type of lightning. These are bolts that connect two oppositely charged areas within a single cloud.

Cloud-to-cloud lightning occurs when lightning jumps from one cloud to another separate cloud, but never touches the ground.

Cloud to ground (CG). When a bolt of lightning strikes the ground, it is called cloud-to-ground lightning. CG strikes can be either positive or negative, and is determined by the direction the electrons flow through the bolt.

In a negative lightning strike, negative charges are being transferred to the ground, which is the most common type of CG lightning. When a positive charge is transferred to the ground, it is called positive CG lightning. Positive CG strikes only account for around 5% of all CG strikes, but they can be far more powerful and dangerous than their negative counterparts.

Dry lightning. While thunderstorms normally bring heavy rain, that is not always the case. Dry lightning is lightning that occurs in such a storm; that is to say, a thunderstorm that is not dropping precipitation, or where precipitation doesn't make it to the ground. Because there is no water to quench potential fires, dry lightning is frequently responsible for causing wildfires.

Bead lightning. Also called pearl lightning or chain lightning, bead lightning isn't actually a separate type of lightning, but rather the dissipation stage of regular lightning. After a bolt's return stroke, it may appear to decay from a solid bolt to a string of bead-like blobs of light. This happens all of the time, but may not always be apparent and in some cases, may be too quick to see with the naked eye.

Ribbon lightning. Lightning occasionally will have more than one return stroke, which looks like several quick flashes in a the same place. When this occurs when the winds are especially strong, it can actually blow the subsequent return strokes slightly to the side, causing a unique ribbon-like effect.

Upward lightning, or ground to cloud lightning. As the name suggests, this is lightning that appears to originate on the ground or from a tall object on the ground and moves up towards a cloud.

Transient Luminous Events: Jets, ELVES, ghosts and sprites. Although the names may sound fantastical, these are very real phenomenon.

Transient luminous events, or TLEs, are not exactly the same type of lightning you normally see, but are related to it directly. They are a form of electrical discharge that takes place much higher up in the atmosphere above storm clouds, often following powerful positive cloud-to-ground lightning strikes.

All of these various names refer to different types of events, which include tall jets of bright blue light, forking branches of red light, or even faint puffs of green light. Similar to the Northern Lights, TLEs give off different colors of light depending on the various gasses, such as nitrogen, that they excite in the atmosphere.

Ball lightning. Ball lightning is a somewhat controversial subject because in the world of meteorology. Because it is so rare and unpredictable, scientists only really have eye witness accounts and reports to go off of.

Reports often vary, but they usually describe a glowing ball that lasts for many seconds unlike regular lightning which lasts for only a fraction of a second. It has even been reported to pass through walls and windows, even floating around within a house.

There are a number of hypothesis that have been proposed over the years, but nothing definitive has been proven. For now, it remains a mystery!

What causes thunder?

While lightning can be quite the visual spectacle, they are called thunderstorms for a reason! The immense discharge of energy from a lightning strike gives off bright flashes of light, but also generate loud, sometimes deafening, claps of thunder.

When a bolt of lightning flashes, the discharge of energy actually superheats the surrounding air into plasma. This nearly instantaneous transition causes a spike in pressure, which forces the air to expand outward. This outward expansion creates a shockwave, which we hear as thunder.

Because sound travels at a more or less constant speed through the air, you can give yourself an approximate idea of how far away a bolt of lightning is based on how long it takes you to hear the thunder that follows. After you've seen the flash, begin counting (one-Mississippi, two-Mississippi, three-Mississippi) until you hear the boom. Now, divide the number of seconds you've counted by five to calculate how far away the lightning was in miles; for every five seconds, the lightning is one mile away.

This can be a helpful way to determine how close a storm is to you and whether or not you're in any immediate danger. Although lightning has been known to strike incredible distances away from the storm, it is generally thought that six miles is the minimum safe distance. So, if you begin counting and reach 30 or more - you're far enough away to be safe. However, if you don't get to 30, you should seek shelter right away, and stay there for at least 30 minutes, or until the storm passes. This is known as the 30-30 rule!

Facts about lightning

Now that we have a better understanding of lightning, how it forms, and the different types of lightning that can occur, let's take a look at some important facts about lightning!

How many people are struck by lightning each year? What are the odds of being struck by lightning?

It's never pleasant to think about something as terrible as being struck by lightning, but we often hear the odds of some other remote possibility compared to your chances of being struck by lightning. But how likely is it actually?

According to the National Weather Service, 270 people are struck by lightning on average each year in the United States. On average 27 of those lightning strikes are fatal while the remaining 243 result in serious injury, and potentially life-long neurological damage. With that in mind, the odds of being struck in a given year are about 1 in 1,222,000.

How hot is lightning?

It may not come as a surprise to you, but lightning is HOT! In fact, some powerful bolts can heat the air up to 50,000 degrees - five times hotter than the surface of the Sun!

Can lightning strike the same place twice?

Yet another common lightning-related saying you might have heard is, "Lightning never strikes the same place twice." The truth, however, is that

lightning absolutely can strike the same place twice, and some places are more prone to being struck multiple times than others.

For example, this is especially true when we look at tall structures, such as the tower on top of the Empire State Building, which is hit by lightning around 25 times a year!

How often does lightning strike the ground?

ccording to NOAA, lightning strikes the ground an average of 20,000,000 times a year in the United States. Of course, those are only strikes that hit the ground, or cloud-to-ground strikes; the total number of lightning strikes of any kind is at least 5-10 times more.

What to do in a lightning storm: Lightning safety tips

By now, it is clear that lightning is a powerful force of nature - one that can be just as deadly as it is beautiful. For that reason, it's important to understand how to take steps to protect yourself from it!

What to do if you're caught outside when lightning strikes nearby

Be weather aware. The best way to avoid the dangers of lightning outdoors is to be weather aware and plan ahead. Monitor the weather forecast through your local weather broadcast or make use of one of the many weather apps for your phone. If you know that thunderstorms are possible, either avoid making outdoor plans or make sure that if you are going outdoors, you have immediate access to adequate shelter.

Avoid the open and heights. Still, weather forecasts are only so accurate; sometimes an isolated thunderstorm will pop up with little to no warning, even if the forecast says it isn't likely. If you are caught outside, get out of the open and off of elevated areas, like hills or ridges, and move as quickly as you safely can towards a substantial, enclosed structure.

Get out of the water. If thunderstorms are in the forecast, you should avoid any activities on, near, or in the water. However, if you're caught out when a storm pops up, get out of the water and move away from it as quickly as possible.

Move to a car. If no structure is nearby, move towards a car. A car can serve as adequate shelter, provided it has a solid metal top (more on that in a moment).

Avoid tall objects, metal objects. Stay away from tall, isolated objects, like trees - these will not act as shelter and can increase the chances of being injured by lightning. You should also avoid metal objects, like clotheslines, fences, and pipes. It's also a good idea to put your umbrella away!

Spread out. If you are with a group, keep distance between you and the others as you move towards shelter. This can reduce the number of injuries if lightning does strike, allowing others to render aid and call for help.

Don't lie down. Do not lie flat on the ground outside. Lightning can travel through the ground for some distance, and laying flat increases the chances of being affected by a potentially deadly current.

Crouch as a last resort. If you feel or see your hair beginning to rise or stand on end, you are about to be struck by lightning. If no adequate cover is available, crouching in a huddled, baseball-like position with minimal ground contact may offer a very small amount of protection,

but this should not be considered a good or safe alternative - it is a last resort.

What happens when lightning strikes a car?

If

lightning strikes a car with a solid metal roof and frame, it will often travel through the metal frame of the car into the ground. This means that passengers are usually safe when inside a vehicle with the windows up.

However, the damage a bolt of lightning may do to a vehicle can be substantial. Apart from frying any electronics, it can melt rubber and plastics, including tires, which can make driving very hazardous if the vehicle isn't immediately incapacitated.

What if your house is struck by lightning? Are you safe from lightning in a house?

Seeking shelter in a sturdy, enclosed structure is the safest solution when a lightning-producing storm is nearby. That having been said, lightning can and does strike homes and buildings and can present dangers to you if certain precautions are not taken.

When lightning strikes a home, it often travels along pipes, cables, and sometimes the rebar reinforcing the concrete slab or wall. For this reason, never shower, bath, or wash dishes when lightning is striking near your home. You should also avoid interacting with electronics that are plugged into the wall, like a computer. Stay away from walls, doors, and windows as well, and keep the the innermost part of the structure whenever possible.

The damage done to a building or home after a lightning strike can vary quite a bit Sometimes, there is very little damage, yet in other cases, it can be quite destructive. In most cases, fire is the primary concern, especially since it can cause small fires inside walls that you don't notice until they have gotten out of control. For this reason, it's always a good idea to call the fire department after your home has been hit by a bolt.

While buildings are struck by lightning far more often than people, it is difficult to say how likely your home is to be struck specifically; there are many variables, such as your geographic location (whether your home is on a hill or in the open), the height of your home, as well as the height of your home relative to other objects near it, like trees and towers. Fortunately, lightning rods can be added to a home, not to reduce the chances of being struck, but to reduce the harm in the event that it does happen.

What does a lightning rod do?

A lightning rod is a simple yet effective way to mitigate the damage to a structure from a lightning strike. They do not make your house more or less likely to be struck, but rather serve to intercept a bolt of lightning by providing low-resistance, conductive channel for the electricity to flow.

Typically, a lightning rod is a metal rod that is attached to and extends above a building. It is then attached to a copper or aluminum cable, which then attaches to a grounding network. Should a bolt strike your home, it will more than likely only strike the rod, and the current will be carried safely away. However, it is important that the entire system be properly installed to minimize the chances of the electricity jumping or sparking off the system and on to something else in your home.

Even with a lightning rod, not everything is protected within your home; it is possible for the resulting electric field from a lightning strike to ruin electrical systems if something like a surge protector isn't installed as well.

Can lightning strikes do damage to electrical equipment?

Absolutely. Even if a bolt of lightning doesn't directly strike an object, electronics nearby may still suffer damage. In fact, a significant portion of home damage from lightning strikes doesn't actually occur as a result of a direct hit; even a close lightning strike can surge electrical systems, overloading them and potentially causing fires.

First aid for lightning strike victims

Despite the immense power of a lightning strike, people can and often do survive them. However, without immediate emergency medical treatment, their chances are low.

First and foremost, call 9-1-1 and give them details about your location, situation, and anything they might ask about the victim.

Next, it's important to be aware of the continuing lightning danger, not just to the the victim, but to you as well. If the victim or victims are in an unsafe spot, like an open field or near a tall object, you will likely need to move them. Fortunately, lightning victims rarely suffer any sort of injury that would make moving them dangerous, such as broken bones. If they do have broken bones, or if they are bleeding, do not move them.

Lightning does, however, often cause a heart attack, so you'll want to see if the victim is breathing and has a heartbeat. If they are not breathing, you'll need to immediately begin mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. If they don't have a pulse,

you'll also want to begin cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) compressions as well, and continue this until emergency personnel arrive (

according to the CDC). If several people have been injured, look for those who are unconscious first as they are at the greatest risk of dying.

Note: It is perfectly safe to touch someone who has been struck by lightning. They do NOT retain an electrical charge.

Lastly,

burns and

shock are common after being struck by lightning. Treat these with basic first aid until help arrives.

Germania's Spring Storm Series

Make sure you're weather aware this spring storm season - check out the rest of our severe weather blogs!

1. Thunderstorms

2. Hail

3. Lightning (you are here!)

4. Tornadoes

5. Microbursts and Downbursts

For more information about Germania Insurance and our insurance products, request a free quote online, or reach out to a Germania Authorized Agent today!

For more information about Germania Insurance and our insurance products, request a free quote online, or reach out to a Germania Authorized Agent today!